As a winner of all five major Academy Awards (film, director, actor, actress and screenplay), this film has a fairly solid reputation, although I’d argue that this kind of lionisation by the Oscars doesn’t amount to all that much, given how wide of the mark they so often are. But certainly, The Silence of the Lambs is a very tautly made psychological thriller with fairly straightforward horror elements in the way its antagonist, a mysterious figure known for most of the film only as Buffalo Bill, carries out his murderous work. His crimes are being investigated by rookie FBI agent Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster), who on the suggestion of her boss (Scott Glenn, always reliably on hand to play bureaucratic heavyweights) interviews the incarcerated serial killer Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins).

I imagine most of this is fairly well known now already, and certainly the tête-à-tête scenes between Starling and Lecter remain fairly intense, as director Jonathan Demme keeps the camera in close on their faces throughout. The performances too are well-awarded, as Hopkins manages somehow to stay just the right side of camp in the leering delight he takes in all the nasty sordid little details of the crimes, while Foster is upright and believable as a fresh-faced recruit. In fact, much of her role is to be a lone woman in the very male-dominated world of law enforcement, scrutinised far more closely than her colleagues as she goes about her work, and the procedural details the film allows her character are partly so that she can be framed and followed by the eyes of the men around her. That said, there’s an uncomfortable element to both the crimes (all against women of a certain size) and to the depiction of their killer, with the story showing a fascination in his cross-dressing which could easily be construed as transphobic, although details are taken from cases of real serial killers.

Whatever its weaknesses, the resulting film is still a fine display of filmmaking craft which manages after 20 years to hold up rather well (hairstyles and fashions amongst law enforcement characters remaining fairly restrained, after all) and which will no doubt continue to exert an eerie fascination for future generations.

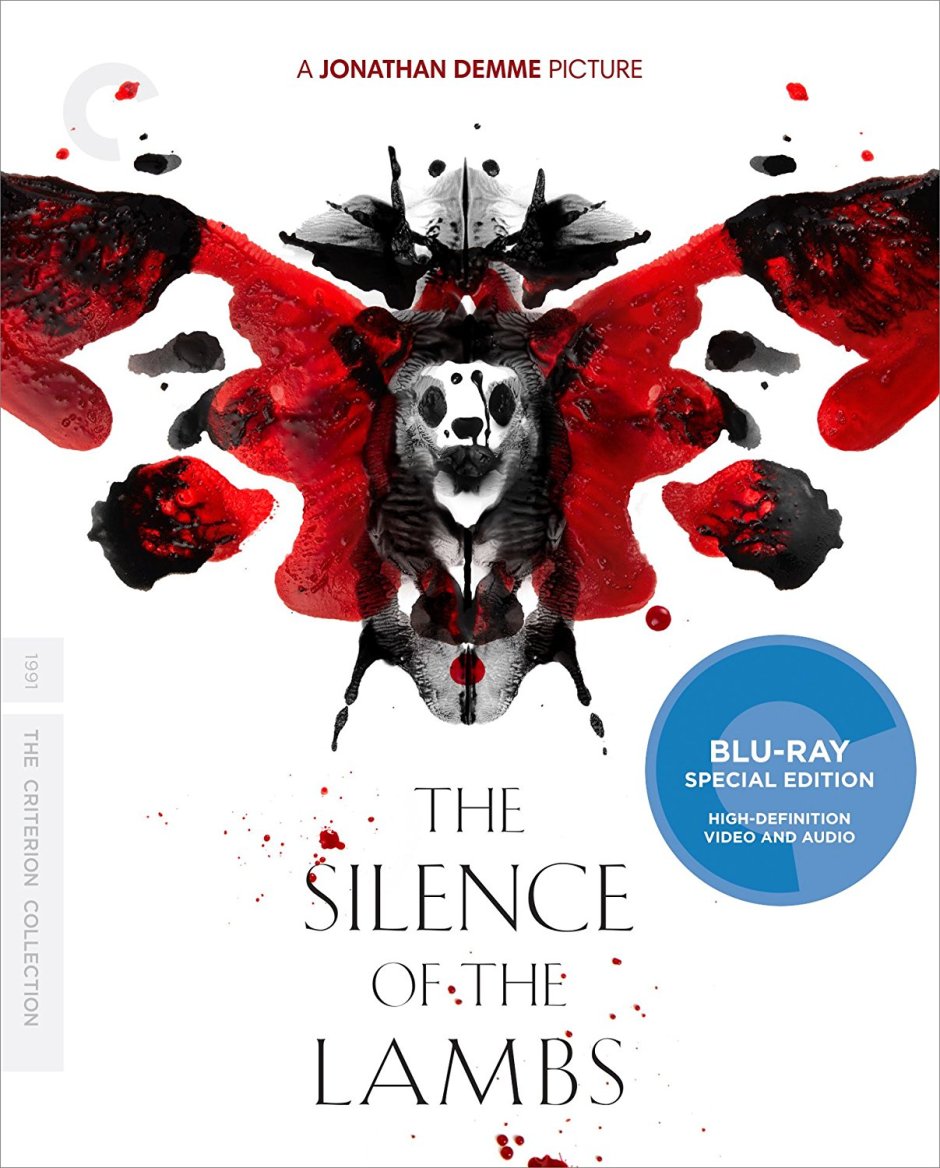

CRITERION EXTRAS:

- The extras on the disc include storyboard comparisons, text from the FBI manual detailing some grisly case studies of serial killers, some lengthy deleted and extended scenes (all nicely contextualised within the film by introductions).

- There’s a commentary featuring the lead actors and creative personnel as well as an FBI agent and is carefully edited and marshalled. It’s largely interesting, though the FBI agent doesn’t have much time for liberal handwringing about capital punishment. Another side effect of listening to a commentary is that the images come into greater focus shorn of the soundtrack, and you really notice the way Demme so frequently frames the faces frontally in dialogue scenes. The cinematography by Tak Fujimoto is also really excellent, with good use of light and dark and almost a softness to the palette.

- NB There’s been a new Blu-ray release of this film since the review above was written, so the extras may differ.

CREDITS

Director Jonathan Demme; Writer Ted Tally (based on the novel by Thomas Harris); Cinematographer Tak Fujimoto; Starring Jodie Foster, Anthony Hopkins, Scott Glenn; Length 118 minutes. Seen at a friend’s home (DVD), London, Sunday 7 December 2014 (as well as years before in Wellington).