So much for writing separate posts for everything; that didn’t really work out for me in the long-term. I still watch a lot of movies (more than ever) but in terms of writing I go through phases, as I’m sure many of us who try and write about films do, and right now I’ve not really felt an urge to write up my film reviews (beyond a few short sentences on Letterboxd). So here’s a round-up of stuff I saw in May. See below for reviews of…

New Releases (Cinema)

Captain America: Civil War (2016, dir. Anthony Russo/Joe Russo). Surely many people are in the same position as me, of now being quite emphatically weary of superhero movies. I’d largely sworn off them this year (hence no X-Men: Apocalypse for me, no Batman v. Superman), but I dragged myself along to this third Captain America film (more if you include the Avengers ones which also feature most of these characters) because I’d liked Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014) more than many other superhero flicks. Needless to say the demands on “fan service” (catering to the fans by featuring storylines for all the characters, which by now is getting to be quite a few) made it overlong, but there was a general avoidance of extended city destruction and it grappled with more complex moral issues than most of these films manage.

Everybody Wants Some!! (2016, dir. Richard Linklater). I saw this twice, because I wanted to be sure whether I really liked it. Granted, it has some serious problems, not least an overly affectionate regard for a group of people (and an era) some might say is beyond reclaiming. That affection goes for unironic female nudity (thankfully fairly brief) and lusty testosterone-fuelled sporting men (though that’s in the title), and yet I still find Linklater’s ability to put together a film pretty peerless, and for all that they were unlikeable characters (for the most part), I found it likeable watching these baseball players through Linklater’s fairly soft-focus filter.

Evolution (2015, dir. Lucile Hadžihalilović). Seen for the second time also; I’ve written up my initial viewing at the London Film Festival last year. Still beguiling and mysterious, though even at its short running length and for all its excellent qualities, the sense of creeping dread and its ominous atmosphere means I don’t think I’ll be revisiting it again in a hurry.

A Flickering Truth (2015, dir. Pietra Brettkelly). A documentary about the beleaguered Afghan film archives, and their attempts to preserve a film heritage which has suffered through various regimes and bitter warfare. Plenty of dusty shots of picking through rubble, and quite affecting in its interviews with long-standing workers there, who’ve dedicated their lives to these films, though it never really lifts off as a film.

Green Room (2015, dir. Jeremy Saulnier). I wrote this up already here, though already its tinged with melancholy at the passing of its star Anton Yelchin. Now that it’s sat with me for a little while, I think if anything I may have underrated this gory siege film: it may not appeal to those who dislike this kind of content, but it’s done a lot more ably and interestingly—and stylishly—than many of this genre.

Heart of a Dog (2015, dir. Laurie Anderson). A strange little personal documentary by musician/artist Anderson, who narrates a digressive story made up of animation, home-shot footage and various other media, in an attempt to deal with loss—ostensibly of her beloved dog, but at a wider level with her husband and with her own mortality. It seems too ragged to work initially, but it has a cumulative power.

As Mil e Uma Noites: Volume 3, O Encantado (Arabian Nights Volume 3: The Enchanted One) (2015, dir. Miguel Gomes). I wrote this up with the other two already here. A bold experiment which didn’t entirely captivate me as it did other critics.

Money Monster (2016, dir. Jodie Foster) There’s an oddly old-fashioned feel to this movie, perhaps because it harks back to Network and Broadcast News and other such newsroom-set movies. The hostage situation that TV host George Clooney finds himself in helps to draw in arguments about modern capitalism and recent financial woes, but in the interplay between Clooney and his producer Julia Roberts, this remains largely a story about a news anchor handling a complex situation. Like Our Kind of Traitor below, it may not be a major work, but it’s an enjoyable watch.

Mon roi (aka My King) (2015, dir. Maïwenn). This relationship drama between Vincent Cassel’s self-assured chef and Emmanuelle Bercot’s (rather unbelievable) lawyer proceeds at a rather strained tempo. It’s not inherently bad, but your tolerance for melodramatic fireworks and exuberant Acting may affect how much you like it.

Our Kind of Traitor (2016, dir. Susanna White). A straightforward spy thriller with the terminally dull Ewan McGregor in the lead, though Naomie Harris as his wife is excellent, and Stellan Skarsgård runs away with the film as a Russian mobster/money launderer. Because of these performances, it’s actually a lot better than one might expect, and certainly passes the time ably enough.

Special Screenings (Cinema)

La Révolution des femmes, un siècle de féminisme arabe (Feminists Insha’allah! The Story of Arab Feminism) (2014, dir. Feriel Ben Mahmoud). It presents a broad sweep for an hour-long film and it does its best to fit in some key historical events and personas for a broad audience presumably unfamiliar with the subject. There are some interviews from interesting perspectives on the key issues as the film sees them, although these are predominantly polygamy and the hijab, which given the preponderance of French commentators is a little loaded. The audience I saw it with (primarily academic) came to the consensus that it was pretty simplistic, and notably omitted any class-based issues, not to mention focusing on key male figures in the early history. However, as a basic intro you could do worse, and it’s good to see another perspective on a narrative of Islam that doesn’t cleave to the usual subjects.

Hamlet liikemaailmassa (Hamlet Goes Business) (1987, dir. Aki Kaurismäki). A pendant to the BFI’s months-long Shakespeare season is this Kaurismäki film, which in its preponderance of plot puts it a little out of pace with his other films. That said, it still retains a mordant deadpan humour that works rather well, at least at times.

Losing Ground (1982, dir. Kathleen Collins). I was trying to work up a review of this film, but I find it difficult to capture my feelings upon seeing it. More or less rescued last year by Milestone Video, the founders of that label provided a brief introduction. It’s one of the earliest feature films by a Black American woman (who sadly died only a few years after making it), and certainly doesn’t lack for the quality of its acting, or its unusual setting amongst fairly comfortable middle-class intellectual couple (she is a lecturer, he a painted)—indeed, eschewing the usual ghetto/violent setting of most African-American films probably didn’t help its commercial prospects at the time. In any case, I immediately bought a copy on DVD and advise anyone else to try and watch this film. Some of its technical qualities seem a little ropey, but it has a great energy and a keen visual eye.

Radio On (1979, dir. Christopher Petit). A ‘mystery film’ screening at the Prince Charles Cinema, and it’s fair to say many of the audience were probably expecting something a bit more trashy, but Petit’s homage to German road movies (à la Wim Wenders) still has a sort of slow-burning spell of gloomy depressing English towns appropriately filmed in monochrome. It’s hard to make out all the dialogue, but there’s an energy to its peripatetic aimlessness which is helped along by the choice of music (Bowie, Kraftwerk, all the usual suspects)—well, aside that is from a cameo by one Sting.

Trouble Every Day (2001, dir. Claire Denis). A new feminist collective focusing on horror movies (the Final Girls) put on this screening as the introduction to their project, and as a fan of Denis’s work, I felt I should catch up with it. It’s a gory horror film with a hint of vampirism, but suffused with slow-mounting threat (though just looking at Vincent Gallo’s face will achieve that nicely). When it does go gory, nothing is held back, and the mood of frank eroticism only makes the bloody turns the more upsetting. Moreover it’s shot with a lot of extreme close-ups and a grainy weariness that only enhances that lack of distance. It seems to be saying something about the way love is (literally) an all-consuming passion, and in depicting that it certainly doesn’t pull any punches.

Home Viewing

Cold Comfort Farm (1995, dir. John Schlesinger). Broadly likeable in its way, though at times I couldn’t tell if it was going for warm-hearted satire on the ways of simple country folk, or nasty-edged class-based caricaturing of the yokels. Of course, Beckinsale’s Emma-like central character is little better, yet on the whole it remains fairly light in tone.

Desperately Seeking Susan (1985, dir. Susan Seidelman). You don’t expect a mid-80s US film to recall Céline and Julie Go Boating, but then again why not? The playfulness and feminine camaraderie of that Parisian film transfers well to NYC, and the stars here never looking anything less than glorious—of their time, yes, but never ridiculous. It’s a film about performance and having fun and in the process finding out what you want. It’s a delight.

Down with Love (2003, dir. Peyton Reed). I’ve reviewed this already here, but to recap based on yet another viewing, it’s a hugely underrated masterpiece of 2000s retro filmmaking which both delights in the costumes, set design, and possibilities of the widescreen frame which come from its early-60s NYC setting (although somewhat conflated with the 50s) via Doris Day comedies, Frank Tashlin satires and a hint of Nick Ray. Yet this isn’t ultimately nostalgia exactly—there are plenty of ways in which the zippy dialogue hides darker unpleasant facets to the era’s sexual politics. But chiefly this is a film whose real stars are its (nominally heterosexual, but that’s part of the satire one suspects) supporting players David Hyde Pierce and Sarah Paulson, so utterly perfect and so brilliantly played that even my usual dislike for McGregor and Zellweger is forgotten—though in truth, their goofy smiles fit the material quite well. Ah, “Catcher Block. Ladies’ man, man’s man, man about town.” I love this film.

Lemonade (2016, dir. Kahlil Joseph/Beyoncé Knowles Carter). I’ve listened to the album a lot since first watching this and it strikes me the film is quite a different proposition. If you can believe the album is just about her and Jay-Z you can’t really take that from the film, which broadens the focus, and really allows for a range of black stories and experiences, moving from the specific to the political. It’s ravishing, raw and moving, and it’s definitely one of the best films of the year.

Lovely Rita (2001, dir. Jessica Hausner). As a big fan of Amour Fou, it’s interesting to watch this early film by director Jessica Hausner and identify some stylistic continuities. There’s a stillness to the way scenes play out, an affectless quality to the acting, and underlying it all, something utterly morbid. Here though there’s an ugly visual texture which may be due to financial constraints but which is completely embraced and even feels right for the story—little tics like the quick zooms and the self-conscious acting which suggest dated and cheesy TV soaps. It makes the way the actions of the title character unfold that much more surprising, even shocking. It’s an interesting debut in any case.

लक बाय चांस Luck by Chance (2009, dir. Zoya Akhtar ज़ोया अख़्तर). A likeable amusing behind-the-scenes take on Bollywood, ahem, the Hindi film industry. It’s a classic tale of the little guy getting a big break and (almost, maybe) getting corrupted in the process. If I were better versed with the context I’d have picked up on a lot more of the celebrity cameos and maybe a bit of the satire, but it all still works very nicely.

My Life Without Me (2003, dir. Isabel Coixet). There’s a little clunkiness to some of the meaningful symbolism, but as far as films about women tragically dying young this is about as good as they can get, and its probably just as well it wasn’t directed by its producer Pedro Almodóvar. There’s a small dose of whimsical magic realism but it’s mostly grounded in the acting, primarily Sarah Polley and Mark Ruffalo.

Pasqualino Settebellezze (Seven Beauties) (1975, dir. Lina Wertmüller) I was all set to detest this film at the start, with its grimy 70s palette and more to the point a protagonist who is vain, brutal, nasty, misogynist trash. And yet somehow it becomes something different by the end, as he undergoes a gradual dehumanisation when captured by the Nazis, as all of what he considered his integrity and morals (very little he had too, mostly around ‘protecting’ his sisters) are stripped from him. I’m not convinced by the use of concentration camps in this way, as it seems like a cheap exploitative means to making a moral point, but there’s no winners here after all so perhaps I’m overthinking it. In any case, it achieves some kind of cumulative power that is affecting.

Picture Bride (1994, dir. Kayo Hatta). A sweetly sentimental film about early-20th century Hawaii and the practice of arranged marriage, focusing on city girl Riyo transplanted to a sugar plantation with a much older husband and coming to find some value in the life there. Nice performances and a surprise cameo by Toshiro Mifune as an ageing benshi.

She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry (2014, dir. Mary Dore). A very solidly made documentary about second wave feminism in the US which nimbly flits through a range of issues from a variety of women (of many races and classes), and also looks at some modern expressions of feminist action. I think it does a particularly good job of celebrating and honouring achievements while also acknowledging the range of opinions which exist (and have existed), and that continued action is necessary. It is ultimately about a certain period of history, but it’s not kept in isolation. There are still plenty of stories to tell.

Sisters in Law (2005, dir. Kim Longinotto/Florence Ayisi). Kim Longinotto tells another fascinating story of women in marginalised spaces fighting for rights, this time in Cameroon. There’s clearly a wider picture of a society based on ‘traditional’ values trying to change, or rather being pushed to do so by the strong women of this story (whether those bringing charges of assault, rape and the like, or those defending them or judging their cases). However the film really focuses in on these key four stories and follows them through, and it is in its way, after all the detailed accounts of abuses heard earlier, a heartening one.

Star Men (2015, dir. Alison Rose). A likeable documentary in which four British astronomers reunite in California 50 years after first meeting one another. It touches on the professional work and research each has done, as well as their respective personalities, and cannot help but address mortality. The filmmaker inserts herself as a sort of fan into the storyline, and her style (particularly with the music) seems to recall Errol Morris. Rather devolves into an extended hiking sequence towards the end, but does have some lovely nature photography not to mention some nice insights along the way (not least that evolution demands death to allow new ideas to take root, an observation by one of the elderly men).

Their Eyes Were Watching God (2005, dir. Darnell Martin). A very creditable film about one woman’s self-determination and struggle to find her identity in the American south, based on Zora Neale Hurston’s great novel (which I was reading at the same time). It’s made for TV and as such feels a little airbrushed around the edges (nobody really ages much despite its sweeping span), pushed perhaps more than it needs to be into a certain generic mould for such stories, but the acting is excellent across the board and the film is beautifully shot.

Underground (1928, dir. Anthony Asquith). Excellent Tube-set London melodrama with a love triangle which goes awry. Expressive camerawork with a fine new score by Neil Brand.

L’Une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings, the Other Doesn’t) (1977, dir. Agnès Varda). There’s something almost disarmingly sweet-natured to this film about politically active 70s French feminists, but perhaps that’s the prevailing hippie vibe of its lead actor who travels around the country in a van singing right-on songs about a woman’s right to choose. It’s a good film though and it still looks great, with vibrant colours and a keen eye for framings. Its political message too is warmly inclusive while celebrating the right to a legal abortion.

Visage (Face) (2009, dir. Tsai Ming-Liang). Every great director has their self-indulgent French film which premieres at Cannes and promptly disappears (well it passed me by at the time). It’s a typically visual film, with scenes that don’t seem to hang together, except perhaps as notes towards an essay on grief, loss, the passage of time, artistic creation, things like that. It has a lot of Tsai’s familiar motifs (it basically kicks off with a deluge) and has plenty of French acting greats. An interesting work that would probably benefit from being seen on a big screen.

زیر پوست شهر Zir-e poost-e shahr (Under the Skin of the City) (2001, dir. Rakhshan Bani-Etemad رخشان بنیاعتماد). I found the narrative a bit difficult to follow at times, but basically it’s about a poor family whose son is struggling to make a better life for himself. Gets a little overwrought at times but mostly is a fine domestic drama.

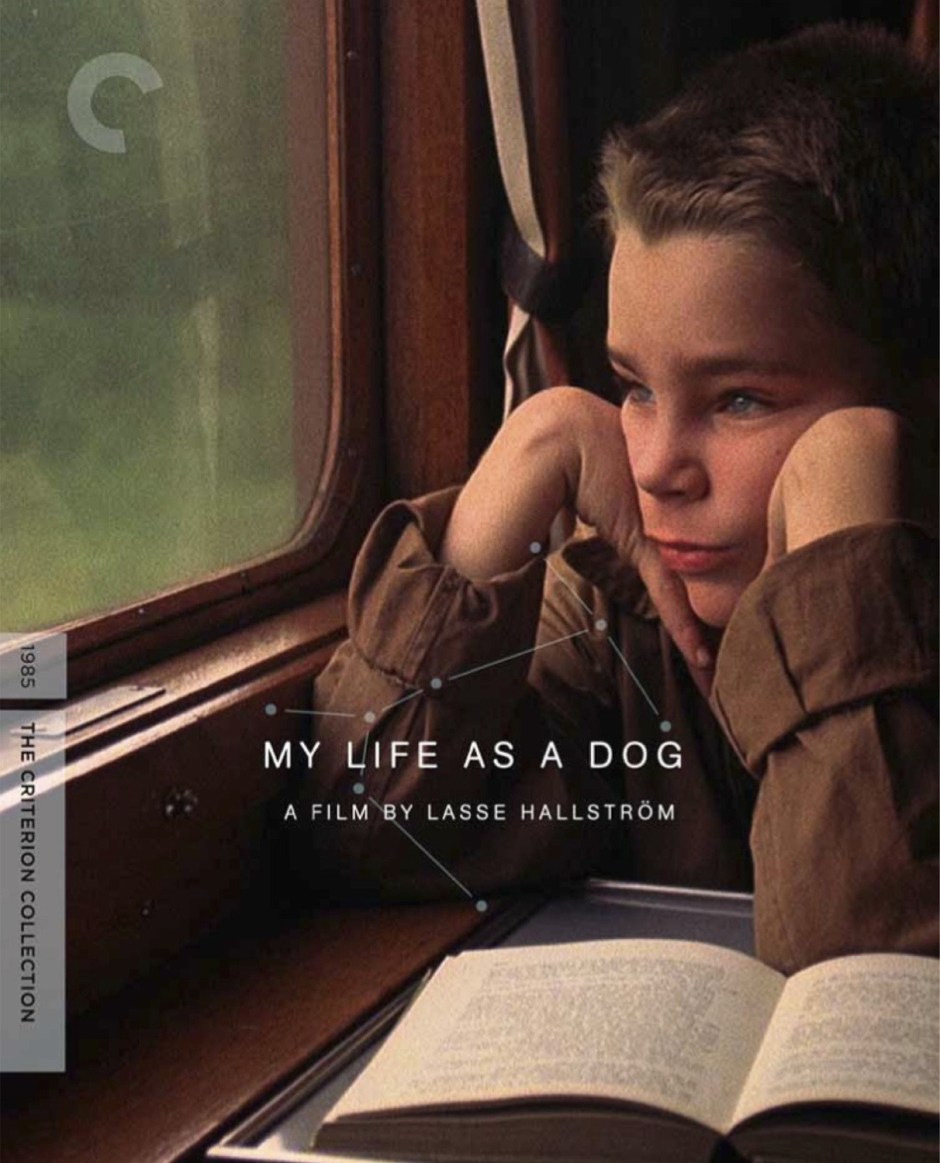

Criterion Collection Home Viewing

I also watched Ivan the Terrible (1944/1958, dir. Sergei Eisenstein), L’avventura (1960, dir. Michelangelo Antonioni), Pygmalion (1938, dir. Anthony Asquith/Leslie Howard), Do the Right Thing (1989, dir. Spike Lee) and Gimme Shelter (1970, dir. Albert Maysles/David Maysles/Charlotte Zwerin) as part of the Criterion Sunday series, but you’ll have to wait for those reviews.